Hadrien T. Saperstein, Researcher at Asia Centre.

Executive Summary

- The Defence Technology Institute’s political and operational impact was blunted since its inception due to an inability to forward works to industrial production itself a result of budgetary constraints and an absence of a legal personhood.

- After the structural reforms (2019), though, the Institute transitioned from a peripheral actor to a resounding voice inside the Ministry of Defence, evidenced by a sustained monetary support for research and development despite an overall reduction in the defence budget and recently receiving the 2021 Organisation of the Year award in the national security sector from the Thai Privy council.

- The Institute made great strides in the (1) unmanned vehicles system tech., (4) simulation and virtual reality tech., and (5) combat vehicles and weapon system tech., but there remains much improvement left to be had with its (2) rocket and guidance missile tech. and (3) military information and communication technology. It has shown overall a real capacity in most instances for successfully moving across the concept to production chain.

- The Institute is likely to continue increasing its standing within the Ministry in the future, due to the country-wide public support for science and technology, unless it becomes unable to follow through on its ongoing projects and export technology abroad over the coming years.

- The Institute should take care not to expand to rapidly on its ever increasing wide-interests and ventures, even if pressured by the Thai Cabinet and armed forces leadership, as this is oftentimes the early signal for a failed offset policy implementation programme.

- Still more research needs to be conducted on the history of the Institute, its role in shaping the Thai defence industry since its founding and its presence as a political actor immersed amongst the factionalism and clientelism existing inside the Ministry and armed forces.

Introduction

On the 28th of October, 2021, the Thai Ministry of Defence’s (henceforth: ‘Ministry’) Defence Technology Institute(henceforth: ‘Institute’) organised a one-hour long webinar on Thailand’s domestic defence industry. Along with that, the webinar provided foreign observers and investors a rare glimpse into the inner workings, endeavours of the Institute over the last several years and its and aspirations and ambitions over the coming years ahead. This webinar is exceedingly timely with its arrival on the back end of a third Covid-19 wave that has almost crippled the Thai economy and, with it, reduced once more (albeit, perhaps, insufficiently) the overall defence spending of the three branches of the Royal Thai Armed Forces (RTArF) along with upending their respective military procurement cycles. This webinar was prompted and actively promoted towards defence industry specialists, manufactures and investors after the Royal Thai Government (RTG) announced that the annual 2021 Defence & Security arms trade show would be postponed until next year (29th of August to 1st of September, 2022), then, returning to its historical location at the Impact Exhibit Centre in Muang Thong Thani, Thailand. The absence of this event—and, to some extent, as Collin Koh, fellow at Singapore’s S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies, suggested at an earlier occasion, its annual “keeping up with the joneses” vanity project—allowed in an auspicious manner for the guest representatives[1] from the Institute a wide berth to speak on a whole range of developments regarding Thailand’s domestic defence industry not otherwise permissible due to political controls in another medium (e.g., trade show). Many of these developments are discussed at length over the following pages.

It is important to remember that there stands a serious absence of academic study on the history of the Institute, its role in shaping the Thai defence industry since its founding, and its presence as a political actor immersed amongst the factionalism and clientelism existing inside the Ministry and armed forces. Case in point, even highly informed and politically mobilised Thai netizens are not even fully aware of the Institute’s existence or activities. The available information and data that does exist—excepting a working report (2017) that was presented at the seventh International Defense and Homeland Security Simulation Workshop in Barcelona, Spain, by Chamnan Kumsap[2]—is moreover limited only to the Institute’s multi-layered media platforms, current/former employees, retired military officers, dedicated domestic non-professional websites, and independent (domestic and foreign) researchers with limited reach and small financial backing due to the secret nature of the technology being researched and developed at the Institute. As a result, this webinar was immensely fruitful and illuminating for it offered external observers and investors a peek behind the not-so-metaphorical iron curtain.

Historical Background

After an arduous materialisation due to the political in-fighting amid the yellow and red shirts crisis that ensued after the ousting of the Thai Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra (2006)—leading to at least three back-to-back administrations (Surayud Chulanont (2006-08), Samak Sundaravej (2008), Abhisit Vejjajiva (2008-11)—the Institute was finally established on the 1st of January, 2009, with an official printed announcement in the Royal Thai Government Gazette.

There is scant evidence indicating that the Institute’s “annual action plans” (2010-2013) around these founding years were widely productive in satisfying the four strategies listed in its Defence Technology Roadmap (2010-2024). The Institute has on a regular footing vehemently repudiated this charge within its internal documents by offering as proof the delivery of a multi-launch rocket DTI-1 prototype to the Royal Thai Army (RTA) at the beginning of 2011: Making it the first research and development operational building of rocket and missile in the Southeast Asia sub-region. It, also, cooperated with the Royal Thai Navy (RTN) to initiate the development project for a test range in order to test future research constructed prototypes. While laudable works, these are a far cry from huge productive gains as stand-alone(s). Infrequently mentioned, though perhaps the most consequential product actually produced during this time period, is the formulation of three master plans (2012): (1) Unmanned Vehicle Systems Master Plan, (2) Simulation and Virtual Reality Master Plan, and the (3) Information Technology and Communication Research and Development Master Plan. This conclusion is grounded in the view that, in following years, like during its eighth year (2016) of service, the DTI released another annual report with many of the master plans successfully concretising works (e.g., successful production and testing of a modified rocket propulsion system). This historical analysis, however, remains an open academic question that necessitates further investigation for subsequent research.

At the end of last year, Air Chief Marshal Preecha Pradabmook, Ph.D., Director-General of the Institute, did however offerone of the first official explanations about the Institute’s works in the early days:

“Over the past years, the [Institute’s] research and development of the defence technologies had included production of prototype weapons for armed forces to try out to ensure the compliance of actual requirements and standards. The Institute’s operations, thereby, involved only production of prototype weapons which were not subsequently forwarded to actual industrial production due to legal and budget constraints” (italics not in original).

This lack of substantive, industrial work was explained in the conference as being due to the absence of a legal personhood and budgetary constraints, as oftentimes has been the case with newly inducted organisations in this Ministry. A secondary explanation not broached in the conference though may be the dearth of constructive communication—or lack thereof—around this time period between the Institute and the Defence Science and Technology Department (DSTD), the latter responsible within the Ministry for operational support of scientific and technological development. The dearth of constructive communication was not likely an issue of redundancy or a clear division of labour, for, as sources inside the Ministry revealed, the former was then solely responsible for designing prototypes and the latter actualising upon them through the industrial production processes already established in a previous era. The initial reason for the dearth of constructive communication was more probably the result of the Institute securing its opening budget of hundred million baht (2009) from the DSTD’s own allocated funds. In time, this may have garnered animosity between the two organisations ultimately manifesting in time a lack of clear understanding of the ends desired by each organisation and in correlation to one another.

Irrespective of the specific causal source(s) of the breakdown, more than a decade later after its founding date, these structural issues led to system-wide structural reforms once the Thai Cabinet ordered a re-organisation of the Institute through the Defence Technology Act (DTA) (2019). The reform was well-received by the Institute’s leadership, given that they wrote the Act internally and later presented it to the public. Furthermore, in some ways, this reorganisation cannot be entirely separated from and must be understood as reflecting the antecedent reorganisation of the entire Ministry and the inner workings of the Office of Permanent Secretary for Defence through the Defence Act of 2008 (henceforth: ‘Act’).[3] Similar to the Act’s establishment of a “new senior military vetting committee,” overseeing high-level military reshuffles above the rank of brigadier general, the DTA saw the formulation and introduction of the Defence Technology Policy Committee (henceforth: ‘Committee’), whose responsibilities range from determining the policies and goals in the operation of the Institute with respect to defence technology and the defence industry; to issuing regulations relating to the characteristics and types of defence equipment and supplies, as well as the criteria, procedures, and conditions for the manufacture and sale of the military equipment and supplies; and, to determining the guidelines in the promotion and support of the role of the public sector and the private sector in carrying out the activities of defence technology and the defence industry. The DTA notably gave the Institute a legal person status in Thailand, too, allowing the Institute to overcome a previous barrier to acting upon its successful and deployable prototypes.

Again from explanations received by internal sources, this process and stated responsibilities were neither intended nor conceived to replace the weak-oversight procurement procedure currently plaguing each of the three branches of the military alike those processes more common amongst certain western military structures—e.g., the Direction Générale de l’Armement (DGA), the latter responsible for project management, development and purchase of weapon systems for the French military. In other words, rather than being an instrument for Security Sector Reform efforts in Thailand (SSR), this process was more so conceived as an instrument to support the military towards satisfying its standing procurement wishes.

Approval of the Committee members has been a slow process going in the last few years. It took more than a year-and-a-half after this reform was passed for the Cabinet to approve decidedly the proposal from the Ministry to (re)appoint a Chairman of the Board and qualified members of the Committee, with General Popon Maneerin once again standing as the official Chairman since August 8th, 2021. The back-and-forth discussion over the Committee members in the Cabinet, engendering the appointment delays, more than likely stems from the 2019 Thai prime ministerial general election that occurred around the time of the introduction of the Act, which, in lieu of a clear winner, manifested a fragile balance of power between vying political parties and military factions inside the Cabinet and military leadership. And yet, despite the Cabinet’s slow process to appoint the Committee, the Institute nevertheless seems to have been able to achieve a variety of projects, discussed in greater detail in the following sections.

The Institute in a New Age of Domestic Defence Investitures in Thailand

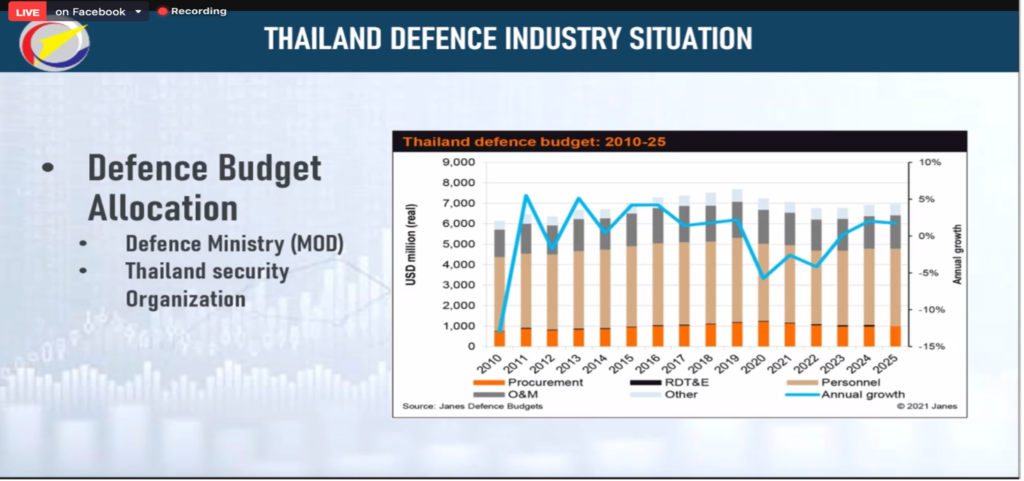

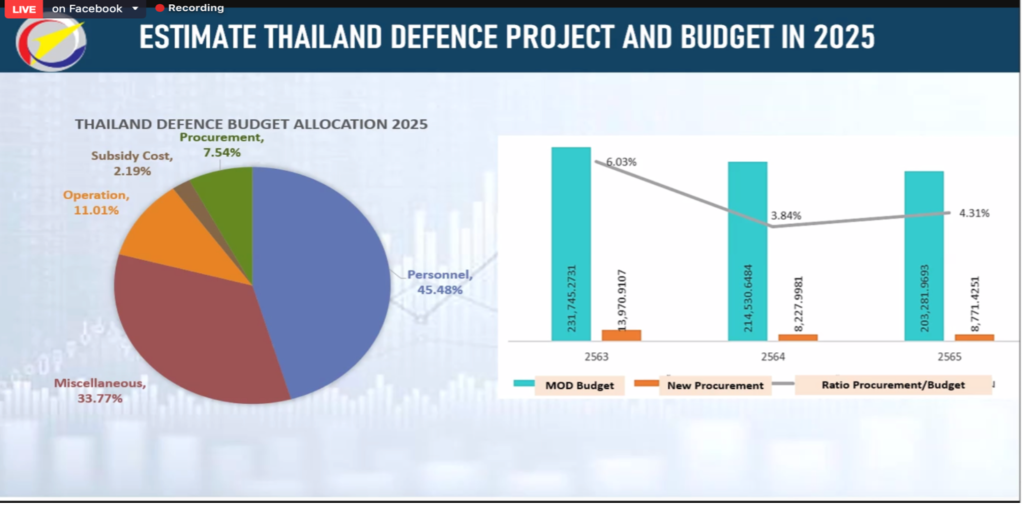

The Thai RTArF defence budget has decreased by roughly 1.4 billion dollars since the start of the Covid-19 global pandemic and not projected to return to its historical (7,000 per million) budget and (5%) percentage of GDP until 2027 (see, appendix 1). As the pie chart displays (see, appendix 2), the RTArF will have to undertake real budget management control over the next couple of years.

Notwithstanding this arduous budget crunch, starting from the fallout of the Covid-19 crisis, the Institute seems to have transitioned from a peripheral actor to a resounding voice inside the Ministry. This conclusion is deduced from two points. First, the research and development (R&D) percentage within the defence budget will remain unchanged and, starting from next year, will actually increase as per the order and wishes of the Thai Prime Minister, Prayut Chan-o-Cha, who, not only stated while attending the 2021 National Science and Technology Fair (9th to 19th of November) that the procurements should come increasingly from domestic sources but advocated that the country should focus on science and technology, too, in order to successfully arise from the economic crisis incurred from the Covid-19 crisis. Second, as internal sources disclosed and photos have revealed, the new Chairman of the Board, General Popon Maneerin, is in close leagues with the Prayut-Prawit (Wongsuwan) faction and the monarchy. Case in point with the latter, the Thai Privy Council—administrative body that advises the monarchy on daily affairs—, through Air Chief Marshal Chalit Phukphasuk, bestowed upon the Institute’s Director-General, Preecha Pradabmook, the 2021 Executive of the Year Award and Organisation of the Year award in the national security sector.

The value of these facts must be tempered to some degree by the recent noted cracks in the relationship between the Thai prime minister and the deputy prime minister—Prawit Wongsuwan. The Institute’s budget and awards still remain prescient, nonetheless, as they emanate as a direct consequence of working within a framework of royal-military-government investments in science, technology, and research-and-development. All this to suggest that the Institute finally appears to be in a somewhat fortuitous political position after a more than twenty-year journey and likely to increase its standing inside of the Ministry unless it is unable to follow through on its ongoing projects and export technology abroad over the coming years.

Case Studies

With the reduction in the defence expenditures across the three branches due to the economic consequences of the global pandemic, the representatives repeatedly stated during the webinar that the Institute was squarely focused on ‘adaptability in defence supply chain.’ As already explained elsewhere, more than anything else, this phrase is coded language for a longstanding ethos and penchant in Thailand’s defence sector for moving away from an import-based defence procurement model towards adoption of an offset strategy: To prioritise technology transfer for defence procurement programs to support the development of local industry. The Institute articulates its own worded efforts to achieve this adaptability by focusing on five technology platforms: (1) unmanned vehicles system technology, (2) rocket and guidance missile technology, (3) military information and communication technology, (4) simulation and virtual reality technology, and, (5) combat vehicles and weapon system technology. Only some of the technology platforms are discussed at length here over the coming pages, so, to fully complete the analysis, to reiterate an earlier point, further research is required over the coming months and years ahead.

Unmanned Vehicles System Technology

The Institute signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with the RTA to develop a medium-range tactical unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) for the service’s Army Aviation Centre (AAC) several months back. The new UAV—D-Eyes 04 (medium tactical UAV)—is intended to be a large step forward from the previous generations—D-Eyes 01 (multi-rotor UAV), D-Eyes 02 (mini UAV), and D-Eyes 03 (small tactical UAV)—and replace the RTA’s Searcher Mk II UAVs, non-domestically manufactured by Israel Aerospace Industries and been in operation since the early 2000s, which itself replacedthe squadron of R4E30 that was purchased from the United States in 1982. Although the Institute has yet to announce which private manufacturer will receive the outsourced contract, the proposed design will be based on Chinese firm Beihang UAS CY-9 platform, featuring a seven-metre-long twin-boom airframe with the engine positioned in the rear in a pusher-propulsion configuration, slightly swept-back wings that are about fourteen metres in span, and a chin-mounted electro-optical sensor turret. The Institute will partner with the RTA, who will test the UAV prototypes.

In view of the wide variety of UAV types in the works and already produced by the Institute, it is not unimaginable that the Thai armed forces could in the future organise an UAV task force, as some other armed forces around the world (e.g., United States Task Force 59) are now commencing to coordinate due to the blending of peace and war operations increasingly visiblein the air domain. This operational move would require revisiting some of the noted issues already underlined in another studyon the Thai armed forces abundant shortcomings with the concept of jointness and multi-domain warfare despite systemically placing emphasis on network centric operations.

After a long-awaited inaugural, the Institute finally opened its Unmanned Aircraft Systems Training Centre (UTC) in response to rising demand for human resources development required by the Ministry of Interior (MoI) along with agencies related to national security. This UTC is Thailand’s first to be certified by Approved Training Organisation (ATO) in compliance with regulations prescribed by the Civil Aviation Authority of Thailand (CAAT). Throughout the Remote Pilot Visual Line of Sight Certificate (RPVLSC), the candidates will have the opportunity to operate a RVC multi-rotor—D-Eyes 01. As a complement, on the 20th of October, 2021, Burapha University Chanthaburi Campus held a signing ceremony of the MoU for the training of UAV pilots and develop infrastructure in the Eastern Economic Corridor (EEC) with the Institute to study, research, and develop innovations and technology for UAV systems for exploring natural resources and coastal environments. In addition, the MoU supposedly disseminates academic knowledge and personnel development for both parties. On the other side of the coin, the Institute has quietly. Despite these efforts, though, it must be stated that the RTN has chosen to purchase another lot of the Camcopter S-100 from the Austrian Schiebel company as it had prior to the pandemic (2019).

Along with the unmanned aerial vehicle technology programs the Institute also invested in an unmanned explosive ordinance disposal robot (UEOD-Robot) technology in collaboration with both the Technology Research and Development Co., ltd (Manakorn University of Technology (MUT)) and Prince Songkhla University (PSU). Of note, the latter’s engineering department is getting a reputation for developing robotic technology evidence by the construction of a beach cleaning robot prototype showing some success. Achieved both equally through a consortium model with the Institute, each academic institution attempted to tackle the short supply of spare parts for EOD robots in the Thai military establishment. As the representatives claimed, the EOD teams in the Deep South, Thailand, currently afield are supposedly thrilled with the ten D-Empir V.4 and NooNar robots received. In addition to the EOD teams in Southern Thailand, the older D-Empir V.2.1 has been delivered for trial use to the Internal Security Operations Command (ISOC) Region 4 Police Station. This technology advancement, though, did not prevent the Thai armed forces acquiring seven EOD robots from a Spanish unmanned ground vehicle (UGV) developer—Aunav—last year. The explanation for the order is that the Institute’s EOD robots do not have chemical, biological, radiological and nuclear (CBRN) capabilities at this moment. As part of the Institute’s dual-use technology efforts, starting on the 28th of October, 2021, this same unmanned technology can today also be found in the Department of Corrections’ hospital system due to a dearth of available medical staff left in the wake of the pressures inflicted by the third wave. The Institute delivered two robots (D-Empir Care) with a 5G communication system to Mr. Ayut Sinthopphan, Director-General of the Department of Corrections.

Rocket and Guidance Missile Technology

As written beforehand in others pages, the Institute’s effort to galvanise movement towards designing and producing rocket and guidance missile technology domestically is one of the most crucial roles it has chosen to undertake. The acquisition of domestically produced rocket and missile technologies will allow all of the branches of the armed forces, though, in particular the RTN, to develop a credible program of dissuasion, especially in the case of the acquisition of more than a dozen medium-to-long range, mobile cruise missiles, located along its landed coasts and maritime frontier. The ownership of medium-range mobile cruise missiles would further enhance the RTN’s “defence in depth” and “anti-access/area denial” (A2/AD) or “entrance denial” capabilities.

While in the past there were advanced talks of acquiring the BrahMos-II cruise missiles from India-Russia (450-kilometre range), it appears like little traction has been made on this issue in past months. Internal sources have explained that while the RTN’s Air and Coastal Defence Command (ACDC) remains interested in the technology the central government has not moved on it at this moment, the likely result of a hefty price tag and reduced procurement budgets, as noted above. However, the recent news that the Philippines will become the first country in Southeast Asia to import the BrahMos-II cruise missiles could surely motivate the central government in Bangkok (Krungthep) to act over the coming months.

Amid that context, the Institute has been working over several years on the DTI-2 122mm rocket from Type 85 tracked APC (Armoured Personnel Carrier) for the RTA. In more recent weeks though, albeit not likely in response to the military developments in the Southeast Asia sub-region, the Institute finalised the testing phase of the rockets and placed them in a re-engineered Chinese Norinco Type 85 Self-Propelled Artillery Rocket Launcher (YW306), which have been in service with the RTA since 1987. The DTI-2 is a smaller and mobile version of the DTI-1 (2011) and DTI-1G (2016) rockets that the Institute has designed, built and tested with relative success over the last decade.

Last, the Institute has devoted time and capital working on a weather changing rocket that hopes to prevent dangerous hail from formulating in the air and destroying alimentary crops from those communities highly dependent on their sales for subsistence. The Institute tested these rockets in the presence of the Department of Royal Rainmaking and Agricultural Aviation, as per this department’s mandate since roughly the late 1950s to manage weather anomalies in certain outer provinces. The efforts given to this project is likely the result of the Institute attempting to garner favour with the monarchy as this project was originally initiated by the venerated late-King Rama IX Bhumibol Adulyadej.

Military Information and Communication Technology

The Institute has provided little public information on the development of military information and communication technology in contrast to the other technological categories found in this study. The relative absence of information is likely a two-fold reason. First, this type of technology is less flashy and captures less the imagination of politicians and the national treasury than rockets, drones, and vehicles. Second, its current efforts is tied to the insurgency in the Deep South, Thailand—a highly charged topic amongst the Thai military establishment. What has been gathered here though is that the Institute has been working on research and development of centralized information systems and applications monitoring systems in an endeavour to support operations in the southern border provinces. The quintessential example provided is a license plate detection system used for reading vehicle license plates. Simply put, the Institute’s work on military information and communication technology makes it another governmental institution furthering Thailand’s participation in the global trend of “digital authoritarianism” leading to a less free internet and withering democratic milieu. The only reprieve is that the technology still seems far from flawless but further research is needed as the information appears deliberately concealed from public scrutiny.

Simulation and Virtual Reality Technology

As already mentioned above, the Unmanned Aircraft Systems Training Centre (UTC) and its Remote Pilot Visual Line of Sight Certificate (RPVLSC) has found great success since its opening months back. This, however, is not the Institute’s only simulation and virtual reality technology. It had earlier

constructed and actualised a virtual firing/shooting range (VSR) for new cadets across the armed forces, tanker training simulator for delivery to the RTA’s 21st Cavalry Battalion, a EOD robot simulator to accelerate and improve the quality use of the newly acquired robots mentioned above. All the simulator technology development followed the guidelines established in the regulatory controls of the Office of Prime Minister on Procurement B.E. 2535 (1992). Although these technologies are not exactly the flashiest items on any militaries wish list its successful completion remains an important signifier that the Institute is able to carry out priority projects from the design stage until completion.

These efforts and investments in simulation and virtual reality cannot be entirely separated from the Institute’s efforts and investments in the cyber domain, reflective of a larger trend across the Thai armed forces to prevent further cybersecurity negligence after a massive personal data breach occurred earlier in the year.[4] In recent months, the Institute partnered with a private company—Guardtime—to implement a comprehensive research program to strengthen research in national cyber security, thereby contributing to the Thai armed forces who already recognises in an increasing fashion that cyberspace is the fifth military domain after land, sea, air and space. Through this partnership with Guardtime, the Institute desires to further strengthen its cooperation with the private sector for combat scenarios in the cyber domain. This partnership is intended to provide the entire Thai armed forces with leading cyber defence capabilities. On this new partnership, the Director-General, Preecha Pradabmook, stated that the Institute has henceforward “committed itself to be a centre of excellence in cyber security technology contributing to secure the RTArFs’ weapons system platforms. This collaboration with Guardtime will be the first significant step for the [Institute] in achievement of cyber security capabilities.”

Combat Vehicles and Weapon System Technology

Chaiseri Co., who, through a “collaboration” model with the Institute, transitioned away from its historical manufacturing base (rubber and tires) towards the conceptualisation and manufacturing of the ‘First Win” vehicle series—First Win II Armoured Fighting Vehicle (AFV) and First Win II Ambulance—along with the V-150 4×4 armoured car. As explained during the webinar, in order to initiate the process, Chaiseri Co. established a new working committee with the Institute through the signing of a Memoranda of Understanding (MoU), with a focus to formulate a joint R&D framework. The supposed incentive for Chaiseri Co. to formalise such links is to get assistance in getting access to the international market, receive governmental support, and, most prominently, tap into a government-to-government (G2G) procurement networks that is usually closed off due to armed forces’ individualised requirements.

However, while the First Win II and V-150 have received positive reviews in both the domestic and foreign defence manufacturing industry/sector—i.e., winning manufacturing awards—the number of sales avowed to the public has been less than forthcoming. As is the case with other nascent defence industry programs around the world, the low international sale figures are probably due to targeted markets (e.g., Indonesia, Philippines) whose economies were deeply affected by the economic crises that erupted due to the Covid-19 pandemic. Nevertheless, as GlobalData fittingly highlights, the global multirole vehicle market is still projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 2.25%, from US$5.039bn in 2020 to US$6.295bn in 2030, even in the face of a continuous global pandemic scenario. Therefore, the V-150 and First Win vehicle series still remain possible winners in the future and, thus, a theoretical positive case study.

This effort may finally have found vindication in the past days when a number of photos have surfaced showing fifteen of the First Win series—First Win II, First Win ALV, First Win Command and Military ambulance—being tested before being delivered to the Bhutanese Government for its participation in the United Nation’s peacekeeping mission in Central African Republic (CAR), making them the third international customer for this series after Malaysia (AV4 Lipanbara) (2016) and Indonesia (Hanuman) (2019). The Philippines had cancelled its order due to budget cuts in 2017. Unconfirmed information circulating amongst analysts contends that Chaiseri was first contacted by Kingdom of Bhutan several years ago and has been in constant contact with the Thai firm since then. However, orders arrived just in the year. The order allegedly required Chaiseri to deliver all aforementioned fifteen First Win vehicles within forty-five days after signing the contract.

In addition, the Institute is also developing a domestic 8×8 Amphibious Assault Personal Carrier (AAPC) for the Royal Thai Marine Corps (RTNMC), called the R-600, in collaboration with Panus Assembly Co. and ST Kinetics from Singapore. The design is based on the Singaporean Terrex AV-81 8×8 wheeled armoured vehicle/infantry carrier vehicle (ICV). As it stands, the Thai government has only agreed in principle to purchase an initial five R-600s once the trials are concluded, although it is believed that a requirement for more than twenty amphibious vehicles exists as the RTNMC needs to replace its depleted fleets of US-made Amphibious Assault Vehicles (AAV) 7A1s. The R-600s, for all intents and purposes, should become a central feature to the RTNMC’s amphibious landing operations, since, as demonstrated in a recent training exercise, it is planned to be deployed in the first wave along with the newly acquired Norinco AAV VN-16 from China several months back.

This first wave will hypothetically be followed closely by a second wave formed by an onslaught of Ukrainian-made 8×8 BTR-3E1 APCs, which Thailand purchased in bulk over nearly a decade and rebranded the BTR-3CS (Command Staff). The important role that the Institute played was to enabled these APCs to have C5I (Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Cyber and Intelligence) capabilities, through its partnership with Thales, the latter providing the technology. There is no indication at this juncture that the aforesaid Type 85 tracked APC will be included in this second wave, given that it is a constitutive part of the RTA and not the RTNMC.

Near-Seas and Water-related Technologies

While not combat vehicles, it might be significant nonetheless to mention here the creation of an Offshore Patrol Vehicle (OPV) program by the Institute. The program was initially developed for the RTN but with export purposes in mind. The Institute has frequently stated publicly over the years that the OPV has a large market both domestically and internationally. This seems to have been the right call as the government of the Philippines has been interested in a government-to-government deal for the acquisition of six OPVs for the Philippine Navy amounting to US$600m. In the early days the exact nature of the program was unknown, however, the Institute had signed a MoU with a truck trailer manufacturing company—Cho Thevee—earlier in the year supposedly for the development of an OPV management system. A few days ago though, Jon Grevatt—notable defence observer on Southeast Asia from Janes—penned that the MoU has officially been signed between the two parties on a modified version of the 90m OPV that Bangkok Dock is presently building for the RTN.

In less impressive updates, there are also photos circulating online of a mud push boat prototype recently built and tested by the Institute in partnership with the Defence Industry and Energy Centre (DIEC), organisation within the Office of Permanent Secretary for Defence that plans and supervises the armed forces energy usages, and news about a multi-purpose boat prototype delivered to the RTN’s Naval Fleet Command (NFC) and Naval Special Warfare Command (NSWC). While the former was supposedly designed and manufactured with the aim to reduce natural and environmental insecurity around the country due to the pilling of sewage in the insalubrious city canals, the latter was intended to target five maritime security threats. It is unclear whether the mud push boat was built from a direct request by the MoI, but it has been confirmed that the Institute did indeed respond to a call by the RTN for a multi-purpose vessel.

Conclusion

This study concludes that the Institute’s efforts to ameliorate Thailand’s defence industry are sincerely commendable. It made the right decision early in its formation to invest time and money to organise its epistemological framework with regards to its duties and purposes, revealed in its Defence Technology Roadmap (2010-2024) through the three master plans (2012): (1) Unmanned Vehicle Systems Master Plan, (2) Simulation and Virtual Reality Master Plan, and the (3) Information Technology and Communication Research and Development Master Plan; resulting in the latest iteration focusing on five technology platforms: : (1) unmanned vehicles system technology, (2) rocket and guidance missile technology, (3) military information and communication technology, (4) simulation and virtual reality technology, and, (5) combat vehicles and weapon system technology. The Institute made great strides with its development in (1) unmanned vehicles system technology, (4) simulation and virtual reality technology and (5) combat vehicles and weapon system technology. There remains however much enhancements to be had with its (2) rocket and guidance missile and (3) military information and communication technologies.

The Institute has shown overall a real capacity in most instances for successfully moving across the concept to production chain. This is not entirely surprising given the fact that the Institute makes use of already existing, experienced entities in the market through technology transfers and purchases. The final result being that observers should not witness long lead times typically seen with institutions having to develop the products from scratch.

Yet, its recently announced new ventures—the OPV program and cyber security technology—is a worrying departure from this hitherto narrow focus on more experienced technologies per the mandate of the aforementioned technology roadmap (2010). The potential downside naturally being a reverse of the progress made over the last twenty-years. This position mirrors the conclusion articulated by the main speaker during a recent Jane webinar on offset policies in developing economies: “…mandated participation through offset [policies] seldom delivers self-sustaining competencies in absence of far-sighted stewardship of national capabilities… [requiring] incremental steps towards self-sufficiency with a focus on limited range of domains in which a country enjoys a competitive advantage is more likely to yield sustainable results.” Let’s hope therefore that the Institute is cautious not to move too rapidly through its next bureaucratic ontological evolution.

In a final thought, as Mathew George Ph.D., an aerospace and defence analyst at GlobalData, posits congruently, it will be interesting to see the manner by which the international market responds to the Institute’s future offerings over the coming years and the degree to which it will have an impact on the market and governmental institution alike.

Appendixes

Appendix 1

Analayo Korsakut, “Defence & Security 2021 Webinar: A Glimpse of Thailand’s Defence Industry in 21st Century,” Technology Defence Institute, Oct. 28, 2021.

Appendix 2

Analayo Korsakut, “Defence & Security 2021 Webinar: A Glimpse of Thailand’s Defence Industry in 21st Century,” Technology Defence Institute, Oct. 28, 2021.

–

[1] The guest representatives: (1) Ms. Rungnaree Patchapap—Commercial Business Development Division Manager at the Defence Technology Institute, and (2) Mr. Thanarat Thanasomboom—Defence Analyst at the Defence Technology Institute.

[2] Chamnan Kumsap is a research analyst for the Institute.

[3] Kingdom of Thailand, Organization of Ministry of Defence Act, 2008b (in Thai), Parliament Library, Bangkok, Thailand.

[4] Sivaley Sirirot Borirak, “Standards Development; Cyber Security of the Ministry of Defence,” National Defence Studies Institute Journal 3, no. 3 (Aug. 2015): 19-29. Addendum: A comprehensive study that analyses across the Ministry of Defence the standards adopted internally by a number of organisations, institutes, and departments.