The Ukrainian crisis has generated numerous and intense reactions on the international scene. Some, such as those of certain Asian countries, have been put aside. In this article Jean-Yves Colin discusses Japan’s reaction and the consequences of this crisis on the Japanese archipelago.

The latter can be consulted in its entierty below.

Ukrainian crisis: Japan in line with NATO and the EU

Jean-Yves Colin

4 April 2022

Since February 24, the start of the so-called “special operation” in Ukraine, comments

have been focused on NATO’s and the EU’s reactions as organisations, its members (the US

Germany, France, the UK or Turkey) and, as far as Asia is concerned, China’s attitude in

the extent of its “limitless” and “rock-solid” partnership with Russia.

On the other hand, Japan is generally ignored, as are South Korea and Singapore, countries that have condemned this aggression, but also other Asian countries that abstained from voting at the UN. In this context of indifference, one should however take note of the words of François-Xavier Bettel, Prime Minister of Luxembourg, who warmly welcomed the presence of the Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida at the recent G7 meeting… under the surprised gaze of the TV journalist interviewing him.

The countries that emerged from the break-up of the Soviet Union are little known by the Japanese people. Ukraine, then, was not a priority for the Japanese government. However, this war immediately triggered reactions and comments from both the public and the government -much stronger than duringt Crimea’s invasion in 2014.

-A swift reaction from Tokyo

The Prime Minister’s remarks in the Diet and the Japanese representative’s votes at the UN unambiguously and immediately condemned the Russian intervention. Japan withdrew Russia’s most-favoured-nation clause, froze Russian assets, including the yen reserves of the Central Bank of Russia, and implemented measures relating to the SWIFT network.

On the 11th of March, in order to request an investigation by the International Criminal Court on the situation in Ukraine, Japan joined forty other countries that had already signed the declaration. On April 4th, Fumio Kishida spoke to the press to condemn the massacres in Boutcha, near Kyiv, and asked for new sanctions to be put in place with the international community. In addition to these statements and current sanctions, the assets of four Russian organisations involved in the development of North Korea’s nuclear programme have been frozen following Pyongyang’s recent tests. Hayashi Yoshimasa, Minister of Foreign Affairs, has undertaken a diplomatic tour of the Gulf countries to discuss the crisis in Ukraine, and certainly to secure the energy supplies that Japan needs. Fumio Kishida also asked him to go to Poland to provide logistical and financial support for the reception of Ukrainian refugees. Finally, he declared that this crisis should lead to questioning the functioning of the UN and in particular its bodies such as the Security Council, given Russia’s “scandalous actions”.

A specific point can be highlighted: during the UN votes, the abstention of India, a member of the Quad partnership, disappointed and probably irritated the Japanese government, which has been working for years to bring India closer to the other members of the Quad. Fumio Kishida’s recent trip to New Delhi on March 21st was an opportunity for him to express this misunderstanding. However, the Prime Minister was not heard: during the joint press conference with his counterpart Narendra Modi, the latter mentioned common economic projects when Fumio Kishida called for more cooperation between democracies; but since then, the Indian position has not changed.

In this crisis the Prime Minister has the support of the Japanese people. According to surveys conducted a few days or weeks after the start of the Russian military intervention, more than 85% of the Japanese population condemns and supports the government’s sanctions policy, and more than 91% support the reception of Ukrainian refugees; almost three-quarters of those surveyed also fear that this “special operation” will lead to military action by China against Taiwan. Political demonstrations in support of Ukraine were held in Tokyo and Hiroshima, though with far fewer participants than in some European countries such as Germany, but this type of demonstration is usually rare in the archipelago. It is true that Russia has always stirred up reservations and even hostility on the part of the Japanese people: memories of tsarist ambitions in the Far East, long deportations of Japanese soldiers at the end of the Second World War and the anti-communism of a large part of the population and political parties. More anecdotally, symbolic gestures such as the provision of accommodation by the Tokyo Metropolis, the sending of bullet-proof waistcoats and acts of solidarity with Ukrainian artists were observed, as well as the illumination of the Tokyo City Hall building or Nijo Castle, the former residence of the Tokugawa shoguns in Kyoto, Kyiv’s twin city.

– Renewed tensions over the South Kurils

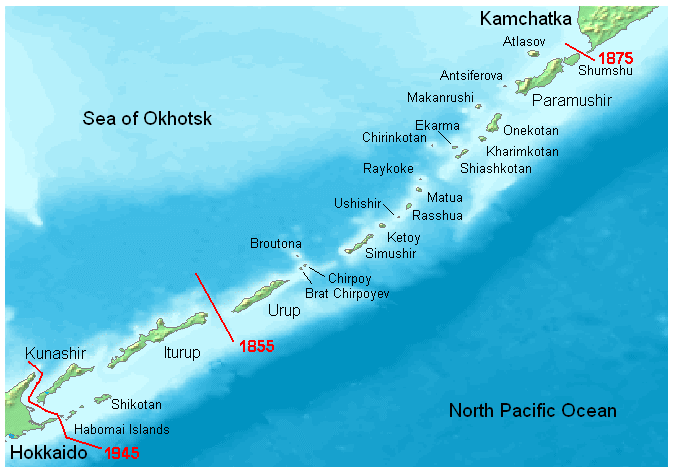

The alignment of the financial sanctions policy with that of NATO and the European Union was qualified as “unfriendly” by the Kremlin, which in response suspended negotiations on a possible peace treaty between the two nations. No treaty was concluded at the end of the Second World War because of the “illegal” occupation of four islands in the Kuril archipelago, which encloses the Sea of Okhotsk between Hokkaido and the Kamchatka peninsula over a distance of nearly 1200 km. The four islands of the Southern Kuril are Kunashiri (Kunashir in Russian), Etorofu (Iturup), Shikotan (Chikotan) and Habomai (also Habomai in Russian); their administrative name in Japan is Northern Territories; they are attached to the Sakhalin Oblast in Russia.

The debate between Japan and Russia over the Kuril Islands is an old one. It dates back to the 17th century and the expansion of one towards the north and the other towards the North Pacific. The Shimoda Treaty of 1855 established the respective influences of the two states: The Russian Empire recognised Japanese sovereignty over the four islands mentioned above and Japan recognised Russian sovereignty over the rest of the archipelago and Kamchatka; the Treaty of St Petersburg in 1875 concluded full Russian sovereignty over Sakhalin Island and the extension of Japanese sovereignty over the rest of the Kuril Islands; at the end of the 1905 Japan-Russia war, Japan, as the victor, was granted colonisation of half of Sakhalin while leaving sovereignty to Russia. The Second World War sealed the fate of the Southern Kurils, as Russia had previously conquered the Kurils after fierce fighting with the imperial forces, notably on the island of Shumchu, the closest to Kamchatka. The 1951 San Francisco Treaty was not signed by the Soviet Union, which in 1946 unilaterally declared its sovereignty over the Kurils. As a result, the Japanese government considered the annexation of the Southern Kurils illegal and the Shimoda Treaty still valid, which was refuted by the Soviet Union and subsequently by Russia. A 1956 joint statement aimed at negotiating a peace treaty raised the possibility of a retrocession of the Habomai and Shikotan islands. It is on the basis of this declaration that discussions between Russia and Japan, and in particular between Shinzo Abe and Vladimir Putin, have continued until today, sometimes with positive prospects for the Japanese negotiators, generally followed by a lack of concrete progress and a stronger Russian presence. Russia has always held out the prospect of a handover of the two islands, accompanied by a partnership agreement on the other two islands of Kunashiri and Etorofu, and possibly all four islands, to facilitate Japanese investments in Eastern Siberia, which the major Japanese trading companies and energy firms were also keen to obtain.

The day after Moscow announced the suspension of negotiations, Fumio Kishida declared it

“extremely unreasonable and totally unacceptable”, especially since Russia has abolished the entry of former Japanese residents of the Kuril Islands without visas (it seems that visits to burial sites are still allowed). Tension has also increased with the announcement of Russian military exercises involving 3,000 troops in the Kuril Islands, including those disputed between Moscow and Tokyo.

– Japan’s eternal energy fragility

Whilst the sovereignty of the Northern Territories is an important political issue for Japan, its energy security is another of great concern. Its leaders have long known that this is a major point of weakness for the archipelago. It was once a justification, among other things, for military expansionism in Asia and the Pacific in the face of retaliation by the United States and the United Kingdom, which the Imperial General Staff considered intolerable. Japan’s energy fragility became topical again during the oil crises of the 1970s. It has become topical again with the war in Ukraine.

Japan’s energy self-sufficiency is very low (7-8% in recent years) and has been steadily declining over the decades, with the closure of coal mines and the temporary shutdown of nuclear power plants after the Fukushima accident in 2011, and of course growing needs.

Since the oil crises of the 1970s, diversification of energy sources and supply has been the watchword of energy policy. While oil accounted for around 80% of energy resources before these crises, its share is now 40%. However, fossil fuels (89%) predominate: apart from oil, gas and coal account for 24% and 25% respectively; renewables and nuclear energy have shares of 10% and 1%. The goal – before the Ukrainian crisis – of the Japanese authorities for 2030 was to pursue this diversification by reducing the share of oil to 33%, stabilising that of coal at 25%, increasing renewables to 13-14% and reviving nuclear power to 10-11%.

Under this allocation, Japan’s dependence on Russia is much smaller than in the case of the EU: Russia contributes only 5% for oil and 8% for gas. Japan buys its oil mainly from the Middle East (Saudi Arabia: 36%, United Arab Emirates: 29% and Qatar: 9%), and marginally from the US (2%). As for gas, Japan is the world’s largest importer of liquefied natural gas, which is the almost exclusive source of the gas it consumes, which it buys from Asia-Pacific (Australia: 39%, Malaysia: 12%), then from the Middle East (18%) and the United States (5%). The Ukrainian crisis is therefore a serious concern for Japan in terms of the disruption of world energy markets, prices and competition between buyer countries.

It is also causing Japan and Japanese companies to question their business relations with Russia. Two major oil companies, Eneos and Idemitsu, have decided to stop purchasing Russian oil products. Out of 168 companies present in Russia, some forty have decided to stop or suspend their activities; others have decided to relocate their factories outside Ukraine because of the impossibility of normal operations, as is the case for Japan Tobacco, which used to produce its Camel cigarettes there, and Sumitomo Electric, which produces electrical equipment.

In contrast, the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) stated on April the 1st that Japan would not make any new investments but would not withdraw from existing ones. He referred in particular to the Sakhalin-1, Sakhalin-2 and Artic LNG 2 industrial projects. He noted that Japan can thus “procure energy at below-market prices” and that a withdrawal – at a financial cost of USD 15-20 billion – would only benefit China. He added that Vladimir Putin’s demand that “unfriendly countries” pay in rubles “should not immediately affect Japan”. The statement followed Shell’s decision to withdraw from S2, in which Gazprom is the largest shareholder (50%), and external pressure, including from Ukrainian leaders. Several companies are involved in these three projects: the trading companies Itochu and Marubeni, Japan Petroleum Exploration Company, Inpex for S1, which was also partly financed by METI funds; the other trading companies Mitsui and Mitsubishi for S2; Mitsui, Japan Oil, Gas & Metals National Corporation for ARC2. The Prime Minister also stressed the need to secure energy supplies.

Like other global banking institutions, main Japanese banks have exposure to Russian credit risk: Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Group, Mizuho Bank and MUFG Bank have announced exposures of 3.1 billion USD, 2.9 billion USD and 2.2 USD billion respectively, but have not yet decided on the provisions to be made given the corresponding uncertainties (rouble repayment risk, asset escrow, etc.).

Other risks weigh on Japan, such as the one, admittedly more anecdotal but sensitive for the population, of the supply of seafood products from Russia, which amounts to about 1 billionUSD and concerns mainly “uni” (sea urchin coral), crab and salmon, all products that are very present in the offer of “sushi” restaurants.

Finally, the Japanese government, like its European and North American counterparts and Asia’s trading nations, cannot but fear the consequences of the war on international trade, supply bottlenecks and shortages or the possible weakness of private consumption and investment. His fear is coupled with that of the return of inflation – an intangible objective of the Bank of Japan for almost 30 years, but not imported inflation for which the monetary weapon is ill-suited – and the discrepancy between the monetary policies of the Bank of Japan and the US Federal Reserve, which weakens the yen without helping foreign trade or growth.

In Conclusion, Japan seeks to fully play its role as a major international power member of the G7 by preserving its interests and security to the best of its ability, while being aware of China’s opportunity to buy up Western assets and the danger of the Sino-Russian partnership. The war in Ukraine led the Japanese government to review its national security strategy, a new version of which is planned for the end of 2022. Indeed, Japan can reasonably feel threatened by three neighbours: China in its regional ambitions in the South Seas and the Pacific Ocean, with its desire for “reunification” with Taiwan and its territorial claim on the Senkaku Islands; now North Korea, with its likely resumption of nuclear tests and current missile tests – one of which recently fell in its exclusive economic zone – and the exclusive economic zone -; and now Russia, with whom Shinzo Abe’s conciliation attempts have failed. After Covid years, the coincidence of this crisis, a series of earthquakes in the north of the country as far away as Tokyo, and the “hanami” periods of cherry blossoms and then “hanafubuki”, the falling of these flowers like snow, can only have troubled Japanese minds and reminded them of the archipelago’s fragility.